Project Apollo: could you pass the test?

- 18th Jul 2019

- Author: Chris Carr, National Space Academy Lead Educator

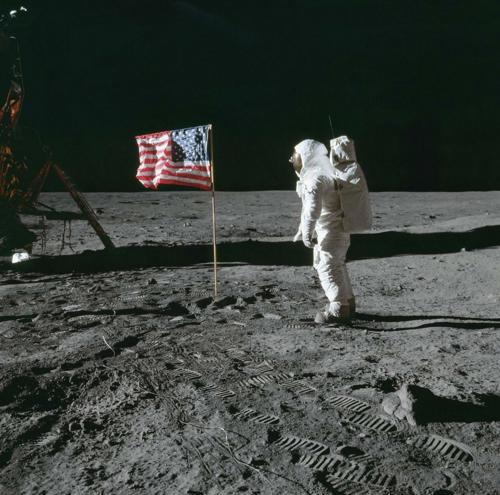

On Saturday the 20th of July 1969, Apollo 11 landed on the moon.

The world was transfixed by what is still to this day, one of humanity's greatest achievements.

Beyond the huge workforce of scientists, engineers and technicians, it is impossible not to be drawn to the three men who shared the cramped confines of the Apollo command module: Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins. What was it about these men that set them apart? What sort of testing did they go through? What were the physical and psychological demands imposed upon an Apollo astronaut? How would you measure up if you went through the same selection process?

We'll look at the NASA astronaut selection process from over half a century ago, which you can adapt for classroom discussion and activities.

Mission to the moon

Project Apollo remains one of the most audacious of endeavours. Against a backdrop of Cold War tension, political manoeuvring, national pride and an anything-is-possible spirit, on the 20th July 1969, humans left the confines of Earth and began the exploration of a new world.

Forever remembered as the 'Mission to the Moon', Apollo 11 was the culmination of several earlier United States test programmes. Project Mercury (1958-63) developed crewed orbital flights. Project Gemini (1961-66) tested and refined many procedures required for a crewed mission to the moon including extra vehicular activity (EVA) and orbital rendezvous.

Just like today, in the 1950s and 1960s astronauts were selected according to strict criteria: The aim was to ensure candidates had the physical and mental agility, and psychological stability, to cope with the expected demands of spaceflight. Aware of the unique challenges that spaceflight could pose, NASA decided to choose candidates from a field of test pilots because they might be best suited to the challenges of piloting experimental spacecraft.

Under the demands of President Eisenhower this field was further narrowed to test pilots currently serving in the military. Ironically, this excluded a certain Neil Armstrong who had left active service and was a NASA civilian test pilot at the time. He would get his opportunity in the second wave of astronaut recruitment in 1962, when this restriction had been relaxed.

Meeting the criteria

Astronaut candidates had to:

- Be under the age of 40

- Hold at least a bachelor's degree in engineering or an equivalent

- Be a graduate of test pilot school

- Be a qualified jet pilot with at least 1,500 hours in command

- Be under 5ft11 (1.8 metres)

- Weigh less than 180lbs (81.6 kg)

The physical requirements were purely for reasons concerning the design of the Mercury space capsule. Astronauts over 1.8 metres would not be able to close the hatch of their crew compartment! Weight restrictions were due to the limited lift capacity of the original Mercury-Redstone launch vehicle.

In early 1959, 32 of the top pilots in the USA arrived at the Lovelace clinic in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Under the direction of flight surgeon Dr William Lovelace, the newly formed National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) formed a selection committee that would oversee an extraordinary battery of physiological tests designed to assess the health of the would-be astronauts.

Over 30 different laboratory tests were performed. They collected data on heart function, brain function and body chemistry. Candidates were subjected to X-ray examinations which thoroughly mapped their body, detailed ophthalmic (eye) examinations and analysis of ear, nose and throat function.

Physiological examinations included testing the candidate's radiation levels, total body water tests, bicycle ergometer tests to measure cardio-vascular fitness and specific gravity tests for each individual. Heart function was scrutinised in every detail imaginable by cardiac specialists. The emerging field of electroencephalogram topography was used to monitor brain activity.

Following this initial range of tests, the field of 32 candidates had been slimmed down to...

...31.

It seemed that the Astronaut candidates were remarkably healthy!

The tests get tougher...

NASA took the 31 remaining candidates to the Wright Air Development Centre in Ohio. During one gruelling week in March 1959, the group were subjected to a wide range of stressful conditions designed to test their capability to respond effectively and appropriately to spaceflight. They included pressure suit, acceleration, vibration, heat, and loud noise tests. Physical endurance tests involved the use of tilt tables, treadmills, blowing up balloons until the point of exhaustion, and placing feet in buckets of ice water!

Physical stress would be one of the biggest obstacles. NASA's mission planners concluded that the heart would be the main organ which would be placed under severe demand on any space mission. Therefore, they designed many of the physiological tests to study the heart's capacity to withstand and recover from stress.

Most of the tests in this article require specialist equipment and resources. However, there are some simple physical tests. In fact, three of those tests used for the Apollo 11 astronauts are commonly used in fitness and physiological tests today: the Harvard Step test, the Treadmill test and the Cold Pressor test.

You might want to adapt some of this to try yourself or with a class but we'd recommend following health and safety procedures and doing risk assessments for all of the tests and adapting them accordingly. Some are examples of aptitude tests which would could be more suitable for the classroom, and some of the physical tests could also be used as examples in P.E. or in problem-solving tasks in maths lessons.

- Performed on a platform of about 50 cm height

- The subject should step up and down from the platform at a rate of 30 steps per minute for a total of five minutes.

- The subject should immediately sit down on completion of the test

- While they are sat down, take their heart rate at 1 minute, 2 minutes and 3 minutes

Calculate the final fitness index:

(100 x test duration in seconds)

divided by

(2 x sum of heart beats in the recovery periods)

A fitness index rating of greater than 96 is regarded as excellent.

- Take three resting heart rate measurements, once a minute for three minutes.

- Set a treadmill at a speed of 3.4 miles per hour (5.47 km per hour)

- The subject walks on the treadmill and the test begins.

- Increase the treadmill incline by 0.9 degrees every minute for ten minutes (incline settings on most modern treadmills can easily be altered).

- During the test, measure the heart rate once per minute.

- After 10 minutes have elapsed, stop the treadmill and measure the heart rate again, once a minute for three minutes.

To calculate a final score:

1. Calculate the number of minutes on the treadmill that your heart rate was under 180 beats per minute

And

Calculate your average heart rate during the test

2. The number of minutes your heart rate was under 180 beats per minute, divided by your average heartrate during the test = n

n multiplied by 1,000 = final score.

The average score for Project Mercury candidates was 75.

One of the more brutal tests!

Equipment: A bucket of ice water chilled to 4°C and a towel. If a bucket of ice water is not available or practical, the Cold Pressor response can still be elicited by placing a finger into ice water in a beaker.

- Whilst the subject is sat in a chair, measure their blood pressure and heart rate once a minute for three minutes.

- Immerse the subject's feet (or finger) into the bucket (or beaker) of ice water for seven minutes

- During this time, measure their blood pressure and heart rate once a minute.

- Once this time period has elapsed, or after the cold becomes unbearable, feet can be removed and placed on the dry towel.

- Measure heartrate and blood pressure again, once a minute for three minutes.

(Even if you adapt this, note that if the cold becomes unbearable you should end the test early.)

Again, a note to please risk assess this activity if you are going to attempt it. Anyone with known blood pressure conditions or heart conditions should not attempt this test for example.

Scoring of this test is more complicated than the others.

1. Take the average of the resting, immersion, and post-test heart rates.

2. Now subtract the average resting heart rate from the average immersed heart rate to find the first key value (P1).

3. Next, subtract the average resting heart rate from the average post-test heart rate to find the second key value (P2).

4. Add P1 and P2 to get your final pulse score.

5. Do the same thing with the systolic measurements and then the diastolic measurements from the blood pressure reading to get your final systolic and diastolic scores. Add the three values together for your overall Cold Pressor test score.

The average score of the candidates was 37.

Once the physiological testing had concluded, candidates were subjected to a range of exercises that tested spatial visualisation, mechanical comprehension and reasoning. A selection of questions can be viewed on iflscience.com but you can see one example from each category below (answers at the end *). Try these out at home, or in the classroom and let us know how you get on!

All images and text for aptitude tests lifted and adapted from https://www.iflscience.com/space/can-you-pass-nasas-astronaut-iq-test/

Spatial visualisation

The first image shows a clock in a set position. From that spot, visualise the timepiece rotating in the direction indicated by the arrow. Decide which answer shows how the clock will look after the rotation.

The test can be made more complicated by adding multiple arrows. To solve this the turns should be visualised sequentially (i.e. the clock's position after move one is its starting position for move two).

What it tests:

Developed in the late 1940s by psychologists J.P. Guilford and Wayne Zimmerman, this exam checks how well subjects picture objects relative to one another. Though the military no longer uses this test, similar ones test how well pilots might stay oriented in mid-air.

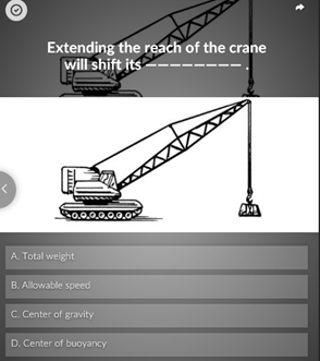

Mechanical comprehension

What it tests: This still-common military exam rates a subject's grasp of physics and mechanics. It assesses how well potential pilots and other recruits apply abstract concepts to practical, real world scenarios

Hidden figures

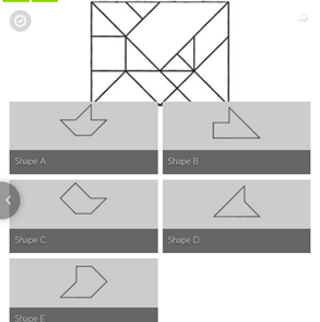

There are five simple shapes, labelled A - E, followed by nine complex drawings, questions 7 - 15. Locate one of the shapes in each drawing (In this example there is one drawing so look for one shape). The polygons will always take the same size and orientation as the original. Answers may be repeated.

What it tests:

This is an adapted form of an original 1926 test developed by German psychologist Kurt Gottschaldt. It is designed to test field independence, of the ability to isolate simple forms in complex ones. Those who spot the shapes might be less likely to get distracted by irrelevant details in a scene.

Matrices

Each question contains three rows of images. The first two establish a pattern, but the last item in the third row is missing, From the eight choices, select the image that completes the pattern.

What it tests:

Psychologist J.C. Raven developed this simple, nonverbal exam to measure deductive ability – making sense of complex data. Unlike many early assessments, this 1936 exercise in pattern recognition has no known cultural or linguistic biases. Today, the matrices are still among the most common question types to appear on intelligence tests.

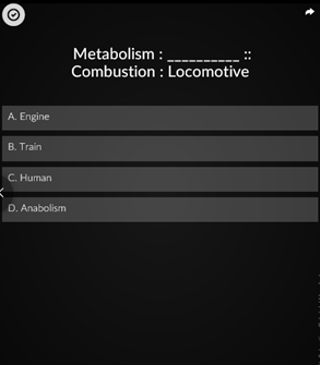

Analogies

In the analogies below, one colon (:) means 'is to', and a double colon (::) means 'as'. Using this logic, select the word from the choices provided that best completes each analogy.

What it tests:

This challenge checks a person's analytical thinking by identifying their ability to make relationships between concepts. It's broad-ranging vocabulary might present problems for those not equally versed in, say, grammar and chemistry.

Though they're an imperfect marker of intelligence, the analogies are a mainstay of tests that value both logical reasoning and broad knowledge.

Testing continued with psychiatric interviews and analysis. Candidates were probed continuously. They lived with two psychologists throughout the full week of tests! A total of 13 psychological tests were used to examine motivation and personality along with dozens of different aptitude tests.

Questions like 'Who are you?' – required each candidate to give 20 definitions of themselves. Candidates were also asked which of their peers they liked the best, which one they would like to accompany them on a two-person mission and who they would substitute for themselves.

At the end of this phase of testing, the astronaut candidates had almost every aspect of their physical and psychological make up probed and profiled – leading one candidate to comment that "nothing is sacred anymore!"

In late March 1959, the final phase of selection began. The NASA selection committee looked over data and reports from all the tests.

Despite the extensive nature of the testing, it proved impossible to differentiate between the candidates to the degree required for selection.

In the end, selection came down to the technical qualifications of the astronauts, the requirements of the programme and the responses they had given at interview.

Finally, NASA selected 7 candidates to become the first astronauts. The 'Mercury 7' were: Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, John Glenn, Gus Grissom, Wally Schirra, Alan Shepard, and Deke Slayton. Together they would pave the way for future generations of astronauts and act as the pioneers for the first crewed space exploration programmes.

In the early days of Project Mercury, it was a possibility that the first astronauts could have been women. In early 1959, Dr Randolph Lovelace conducted his own studies into medical criteria for spaceflight and argued that women would be more suitable for spaceflight as they were generally smaller, lighter, consumed less oxygen and coped better with stress.

Lovelace selected a group of female pilots including Jerrie Cobb, an aviation world record holder, and conducted his own privately funded tests. The women went through the same selection tests as those conducted by NASA.

Known as the 'Mercury 13', this group of women performed as well as any of the male astronaut candidates. Cobb passed all the training exercises and ranked in the top 2% across all the men and women. However, social attitudes of the time meant that these women remained grounded.

American astronauts would remain exclusively male until Sally Ride flew aboard the space shuttle Challenger in 1983. Ride's journey paved the way for more progressive attitudes towards gender and equality; something which the Soviet Union had recognised much earlier:

"A bird cannot fly with one wing only. Human space flight cannot develop any further without the active participation of women"

Valentina Tereshkova, first female Cosmonaut, 1963

You can read more about the Mercury 13 here, in a blog post written by Dr Tamela Maciel at the National Space Centre.

From Mercury to the Moon... and beyond

As the United States space programme continued to develop, the original seven astronauts would be joined by a second and third wave of recruits (the 'new nine', including Neil Armstrong and 'the 14' – including Michael Collins and Buzz Aldrin). This pool of new recruits would contribute to both Project Gemini and the early Apollo missions, culminating in the first moon landing on 20th July 1969.

Further recruitment would follow with a fourth wave ('the scientists' – the first group chosen for their research or academic experience rather than test pilot credentials) and a fifth wave ('the original 19' – who would bridge across from the Apollo programme to Skylab and the early Space Shuttle era). This completed the full line-up of astronauts who would feature throughout the next decade of US spaceflight.

Broadening the selection criteria to include individuals with a non-test pilot background was the first step towards a more ambitious programme which would not only focus on the technological feat of space travel or a Moon landing, but also on exploration and research.

As one example, Apollo 17 would see astronaut Jack Schmidt exploring the Moon through the lens of a qualified geological scientist. A rock sample collected by Schmidt would be termed 'the most interesting sample returned from the moon', providing evidence that the Moon once possessed a magnetic field.

-

![Chris Carr Web]()

About the author

Chris Carr is a Lead Educator for the National Space Academy. He specialises in applying the context of space to Biology in the classroom.

He is also the Network Educational Lead for Science at STEM Learning.

If you would like to ask Chris a question about anything in this article, or about anything else space and biology related, contact him on c.carr@stem.org.uk or LinkedIn.